|

|

ROMANCING the IMAGE — WRITTEN by ART SNYDER

From Rubberstampmadness Magazine

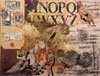

One chapter of The Museum At Purgatory is filled with illustrations of passports, correspondence, receipts and other remnants of a life collected on paper. Another chapter has a continuing border that appears to be a collage, mysteriously running from one page to the next to the next. It's no wonder that this bestseller prompts the question lurking on the mind of every rubber stamper: Does he or doesn't he?

Yes, indeed, he does. Author Nick Bantock uses rubber stamps to create his art.

As with his celebrated Griffin & Sabine trilogy of the early 1990s, Bantock on every page of The Museum At Purgatory continues to ponder the nature of human existence. And as with that trilogy, Bantock seeks answers through the artistic partnership of word and image. This art, created over a two-year period, includes mock mail, collage, found objects, assemblage and beyond, playing two and three dimensions to his theme of life's meaning.

The author, a painter and illustrator by training and profession, uses a philosophy based on Zen, Gestalt therapy and the poetry of William Butler Yeats, and it is through this tri-partite lens that Bantock filters personal meaning. True, reality and imagination play their equal roles in his art, and he invites you, the reader, into this interpretive understanding.

|

|

MOCK MAIL

A quick look through The Museum At Purgatory — or several other fictional works by Bantock in the last 10 years — clearly indicates he is an artist in love with correspondence and the aura of the postage stamp. Even if he has to create his own, as the artistamps indicate.

"I've wanted to do this for ages," he says. "In fact, the original idea for the book was The Post Office At Purgatory. But then it expanded and expanded..."

"I've tried to create [illustrative art] pieces that will appeal to the postal purists as well as those who like lushness and humor. The Penny Black/Red 'bisect' postage stamp [seen in The Museum At Purgatory] is probably the driest of the works, and the most believable. Someone who thought it was real offered me a great deal of money for it. It would be fun to see what would happen to it in auction." (The celebrated Penny Black and Penny Red are the world's first postage stamps, dating from 1840s Great Britain, and a bisect is a postal term. It refers to the once-common practice of using halves of postage stamps of differing denominations, placing them together on an envelope as if they were one stamp — however incongruous their appearance — with a new denomination.)

"I've also used French postage stamp names for some of the characters in my books — Sabine, Ceres and Sage Semeuse. The more you look into the mail between the Utopias and Dystopias [in The Museum At Purgatory], the more loving parody you'll find."

Fittingly, this knowledge of the postage stamp betrays genuine collector's enthusiasm. "My two chief areas of [philatelic] interest are France and Cinderellas," he says, referring with the latter grouping to the issuance of vanity or imitation postage stamps — faux postage or artistamps, if you will. "The more beautiful and obscure, the better."

|

|

|

MAIL ART as OUTSIDER ART

It's not an Olympian leap from philatelic and pseudo-philatelic interests to mail art, especially for an artist who sees these interests as part of a hand-cancelled continuum.

"My origins are fine art, but I remember the first Outsider [Art] show I saw in London," Bantock recalls, in reference to art produced outside the traditional communities of established or academic art. "I was struck by how much power and honesty it held in comparison to the self-congratulatory gallery scene."

"I'd come across mail art before, but never participated, (though an old pen friend insists that I decorated my envelopes when I was 10)."

"Griffin & Sabine was my headlong dive into the world of postal pictures. I did it with a sense of relief, because I realized it was a way to allow people to see images without having to quantify their worth. In Purgatory , I just created a space where I could indulge a little deeper."

Resultantly, Bantock adds flesh to his art-correspondence — mail art in book form, if you will — with a mix of apparently genuine notes, letters and other postal ventures, as well as collaged and other dimensional art created expressly for his latest book. Examples suggest Bantock has embraced the rubber stamp as a viable partner to traditional art media.

|

|

|

RUBBER STAMPS

Logically, these interests in mail art lead many people — artists, especially — to the specific graphics world of rubber stamps, and Bantock is no exception.

"Whenever I can, I buy rubber stamps that relate to the post," he offers. "For a while I tried using rubber stamps for their pictorial content, but I found it limiting. I'm interested in them, not as the direct art itself, but for the way they bond with my images and lend an authenticity to them in terms of time and place," as seen in several chapters of The Museum At Purgatory, not to mention the Griffin & Sabine trilogy and other fictional creations by Bantock during the past several years.

He suggests that rubber stamps offer great flexibility in creating art, as they are "relatively inexpensive and available in all sorts of amazing images." For stamping, either go with monotones or color the stamped images in, he adds. Consider, too, photocopies of images, along with old postcards and postage stamps, to move your stamping into collage.

|

|

|

COLLAGE

For many rubber stamp artists, an evolution into dimensional art, book arts, paper arts and collage is only natural. Such is the case with Bantock. He began his art career with a paintbrush in hand and an easel at the ready, but after nearly two decades as a painter and illustrator, other media spoke to him. It was profoundly liberating.

"Collage has become my easiest form of self expression — it's speed, its adaptable richness and, most of all, the method by which one can switch from order to chaos and back again," Bantock reveals. "Anyone who's read The Forgetting Room will have seen my description of how I make my own brand of collage."

"[Joseph] Cornell, he is a massive inspiration. I just wish I could have as many people hunting for material as he did. Anyone finding neat little 'thingies' that they don't know what to do with is welcome to pass them on to me." [For more on Cornell, see Rubberstampmadness #101, September/October 1998.]

|

|

|

EPHEMERA

The pursuit of collage is the pursuit of ephemera. While Bantock offers no photographic or editorial glimpses of his studio, it's clear that he revels in society's dusty, wasted wants and tattered edges.

"Yes, I trawl ephemera anywhere I can," he freely admits, with some glee. "I prefer to go back beyond my birth. As far as I'm concerned, everything I collect — that which rings the unseen bell! — is useable."

|

|

|

TRANSFORMATIVE POWER of ART

With all these artistic elements in place, the cohesive force of Bantock's world-view — stemming from a lifelong passion for the poetry of Yeats — signals a unity. A unity of birth, a unity of human struggle. A unity of understanding, a unity of compassion. The unity of life."

"Now you're talking about the essence of everything I try to do," Bantock explains, referring to the transformative power of art. "I can't explain it better than in my books."

|

|

|

A PUBLISHING HISTORY

Prior to The Museum At Purgatory, Bantock merged text and image most conspicuously with the release in 1991 of Griffin & Sabine, the book that started the passion for Bantock and leapt boundaries — from Canada to England and Japan, from the United States to Brazil and Australia. It's a story of intrigue, via letters and other correspondence, between the two main characters, Griffin Moss and Sabine Strohem. The interactive, forbidden — nay, voyeuristic — quality of the experience has delighted the world, since each copy of the book contains letters that must be removed from their envelopes, which are affixed to pages throughout the book. There are few sensations that rival reading another's mail, and this brought out the hidden poet and artist in his audience.

Sabine's Notebook, in 1992, was the second installment of the trilogy, followed in 1993 by the concluding release, The Golden Mean. Altogether, with sales in excess of 3,000,000 copies, the three releases have confirmed Bantock's place in contemporary literature, especially with his marriage — an enlightened dependency — of word, symbol and other imagery.

Beyond literature, the trilogy moved Bantock into an enviable place in the art world, a fact not lost on stampers. It is no wonder that rubber stamp artists have developed a near-cult following for Bantock's works, as evidenced by numerous exchanges, mail art correspondences and other stamp-art events on a Bantock theme.

In addition to the Griffin & Sabine inspiration, continued with The Museum At Purgatory, stampers have turned to the Capolan ArtBox, a 1997 release from Chronicle Books. This, well, art-box contains postage stamps — artistamps, to be sure — postcards and the like of a fictional Capolanian government, in honor of their 650th anniversary. It's a treasure-trove of mythology that begs rubber stamp and ink pad reinterpretation.

Bantock is not all mystery, however. Rummage through a children's library and you'll likely find any number of pop-up books that he wrote and devised since moving to Canada. In 1990, for example, There Was An Old Lady saw warm public acceptance. It's based on children's verse from the time of World War I. Despite their relative recent printing, these several pop-up books now are out of print, fully prized collectors' fare. Stampers are likely to get both art and papercraft ideas from any of these releases for the young-at-heart.

|

|

|

THE ARTFUL DODGER

Bantock today plays his studio like a symphony, shifting attention from one work area to another, and back again, juggling projects at hand, finishing one collage, beginning another and contemplating yet another. Then, a dash to the easel in another creative spurt, followed by yet another interest. Beyond the prospects of creating art for its own compelling beauty, as well as the inner peace of the process, he has a schedule from the external world.

"[This autumn] comes The Artful Dodger, a big art book containing virtually all of my art," Bantock says. "Many new paintings, some early stuff from my college days, samples of my book-cover illustrations from the '70s and '80s, the art from the hard-to-find pop-up books, a re-examination of the connections in the Griffin & Sabine imagery and lots more. Also, there will be a whole load of anecdotes related to my experiences in art and publishing."

To be published by Chronicle Books, the large-format Artful Dodger will include 350 full-color illustrations.

|

|

|

HOLLYWOOD

It may seem a whirlwind of improbability since his lean days as a clerk in a betting parlor, but today he is hearing the chorus of Hollywood. With the international success of the Griffin & Sabine trilogy, this should not arch the brow, as a movie based on the characters from that mystifying correspondence is in development.

"The movie has reached second-script stage," Bantock explains. "[Screenwriter] Rick Ramage is doing it, and the first draft was pretty darn good. Only when that's completed can the director and producer nail down the studio and start casting. Could be a week, could be three months. It's Hollywood. Who knows?"

Does more mystery lie ahead? Perhaps. In an appearance this year at a bookstore in the U.S. Northwest, Bantock tipped his hand.

"Yes, I am working on a new trilogy," he noted, to the "Ooh! Ooh!" of his rosy audience.

|

|

|

IN PERSON

Despite hectic art, literature and film commitments, Bantock remains open to personal appearances. "With the tour and preparing to move house (which took place early this year), it's been nuts," laughs Bantock, his tall frame, full head of brown hair and beard commanding attention. In February, for example, he went to Australia on a book tour in the western part of that country. At the Perth Australia's Writers Festival, among other stops, he spoke — appropriately — on a topic dear to many stampers: "Marriage of Image and Texts."

Closer to home, he this year has attended bookstore events from Vancouver to Portland, Oregon, and San Francisco. At Powell's, the gigantic bookstore in Portland, many rubber stampers were on hand, complete with art projects inspired by Bantock's fictional world of Capolan.

"I had a lot of fun with the rubber stamp crew in Portland," Bantock notes with some delight, indicating his growing enthusiasm for stamping as an art form has yet to reveal itself in full. Stay tuned!

|

|

The above interview was reprinted with permission from Rubberstampmadness Magazine July/August 2000 issue #112. Art Snyder is a longtime writer and Contributing Editor. He lives the creative life in Dayton, Ohio.

|

|

© 2024 NickBantock.com

|

For more Pelicos info visit: Collection Art Prices & Order Interview

|

|